| Original title: Sanshô Dayû |

Rating:  (5 / 5) (5 / 5) | |

| Year: 1954 | |

| Director: Kenji Mizoguchi | |

| Duration: 124 min. | |

| Genre: Drama |

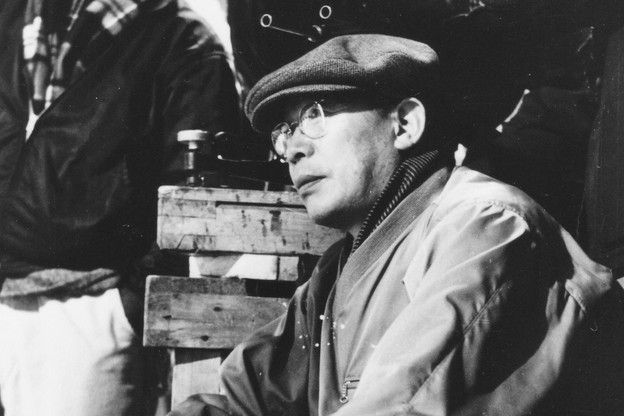

Kenji Mizoguchi

It’s a crime that up until now I haven’t written anything about my favourite director or any of his films yet, so this piece is well overdue. I picked the film that really made a lasting impression on me to try and show what a great director Kenji Mizoguchi (1898-1956) was. But maybe a short introduction is required first. The recurring theme in many of Mizoguchi’s films is the suffering of people and women in particular, mostly at the hand of men. Sometimes these men are like savages, other times they are just foolish or too busy with their own status or money to notice what is going on around them. This both reflects the way of life in Japan at the time, as well as his own life.

As a child his family lost all their money and status, which resulted in his sister being ‘given up’ to become a geisha. It was this sister that would later take him into her home and got him several different jobs. It wasn’t uncommon in those times to have women give up their whole lives to enable men succeed in theirs. Becoming a geisha meant going through years of hellish training and eventually selling your own body and life to men of stature. In the end one could say that if it weren’t for his sister’s sacrifices, he could never have become the successful director he went on to be. And exactly that is what he struggled with his entire life.

Many of his films center around women, often geisha’s or plain prostitutes or normal women forced to become one. They are used, abused, tortured and killed just so men can have a bit of fun in their lives. This may seem very women-unfriendly, but it is really Mizoguchi showing us what life is like and how it should be changed for the better. I fact according to his IMDb page, he may be seen as the world’s first feminist director. Some of the best examples of women suffering can be seen in films such as Ugetsu Monogatari, Yôkihi, The Life of Oharu, but perhaps most in Sansho the Bailiff. Internationally, his greatest success was Ugetsu Monogatari, the film he made before just Sansho the Bailiff.

His career as a director could be divided into three parts. First his 1920 and early 1930 films. During this time he made over sixty films, but unfortunately almost none still exist today. This is the case with many Asian films from that time. They weren’t stored properly, so the film rolls got so badly damaged they were no longer usable. The second part of his career starts with his two 1936 films Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion. As he himself put it, it was only then that he became a serious director. Somewhere in the late 1940’s is when part three would start. This is when he started making all the films we remember him by today. In 1956 Mizoguchi died to leukemia. He is joined by Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirô Ozu as one of the three grand masters of Japanese cinema.

Sansho the Bailiff

The legend told in Sansho the Bailiff dates back to Japan’s middle ages, when mankind had yet to awaken as human beings. Or so the opening credits tell us. Keep in mind that this is an extremely cruel, powerful and somehow also very beautiful film that shows its viewers exactly what the opening credits say. The story being told is one of a family whose lives are brutally torn apart by the many horrible people they encounter. Unlike the title may suggest, Sansho the Bailiff is not primarily about some guy called Sansho and he and his wicked beard don’t even get that much screen time. However he is a key player in the lives of two of the main characters, a boy and his sister.

When the film begins a family must say goodbye to the father – once a noble lord – who is now being forced to live in exile. The mother, her two children and a maid undertake a journey to join him. But disaster strikes when a band of human selling thugs break up the family, taking the boy and girl with them to sell as slaves. They end up working for a rich noble called Sansho the Bailiff. Their mother is sold as a prostitute elsewhere and the maid disappears entirely and is never seen again. In almost any film, this would be considered a pretty bad situation, but here the real suffering hasn’t even started yet.

They boy and girl, Zushiô and Anju, are forced to work on Sansho’s property. It is hard work, and quality of living isn’t very good. This means it is easy to revert to some primal way of living, but their father has always taught them high moral standards. The children feel that they should try to remain true to those standards as best as they can given the situation. But this doesn’t make things any easier. Of course Anju, being an attractive young girl, will be harassed by the men, while Zushiô is forced to do all the hard labour. Meanwhile their mother is somewhere else entirely. Every now and then she tries to run away from her life in the brothel to go look for her two children. When her owners decide enough is enough, they make sure she will never be able to flee again.

This is far from all that will happen in this film, but it should give a good impression. Luckily there is also always this little spark of hope that everything, or maybe just some things, will turn out alright in the end. Aside from a lot of story and plot, there is much more to this film. The acting is absolutely top notch and the scenery, photography and music is of high quality. Another Mizoguchi trait is his use of very long takes. However the film never has a dull moment. Quite the opposite in fact. The slow takes give the audience the time to have a look around, think about the situation for a second and let it all sink in. This works especially well in the magnificent final moments of the film and the scene in which Anju enters the water.