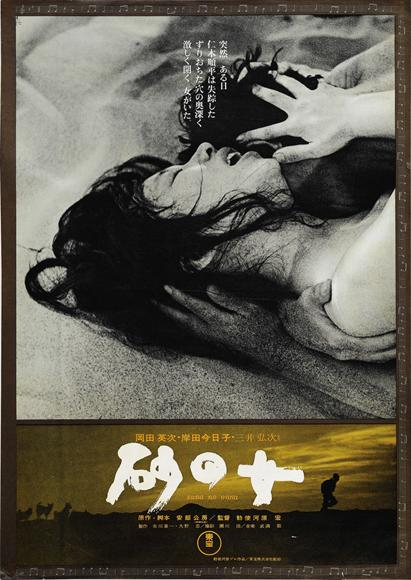

| Original title: Suna No Onna |

Rating:  (5 / 5) (5 / 5) | |

| Year: 1964 | |

| Director: Hiroshi Teshigahara | |

| Duration: 146 min. | |

| Genres: Thriller, Drama |

Woman in the Dunes

Not many films were made by Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara. Three of them stand out. Pitfall (Otoshiana), The Face of Another (Tanin No Kao) and this one, Woman in the Dunes, sometimes called Woman of the Dunes, but I prefer the first translation. All three are highly experimental films in which the director poses some difficult questions about who we are as individuals and what makes our clocks tick. Woman in the Dunes (trailer) makes this most clear by questioning our motives to live. Are we moving sand to live, or living to move sand?

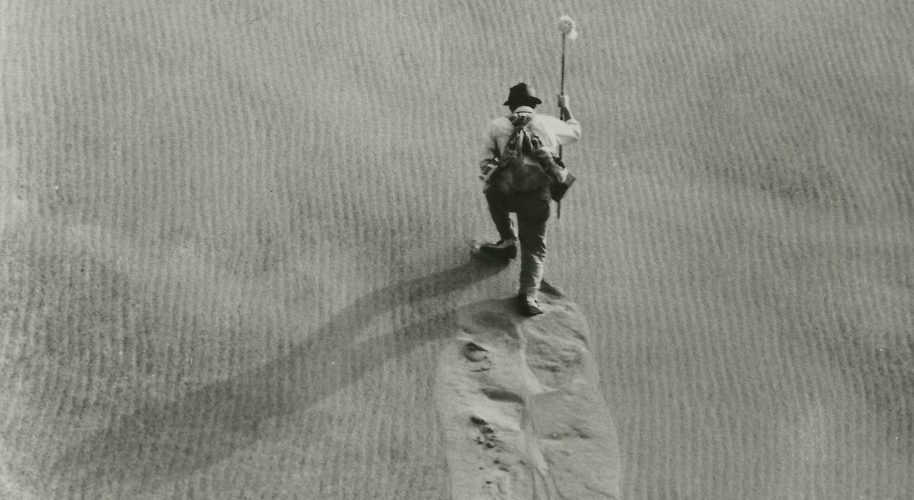

One day a man is looking for bugs in the dunes near a beach. He is there, because city life is unrewarding to him. The absurdity of having a passport, an ID card, a library pass, union cards and all sorts of other paperwork to define who you are is aggravating him. At least discovering a new type of bug, and having your name written in a catalog actually amounts to something real. Or so he seems to think. What happens to him next could only be described as a nightmare. On that starts off with him missing the last buss back to town. He is invited to a small village and can stay the night with a woman who lives down some sort of pit in the dunes.

The woman prepares a humble meal, but everything about the dinner scene feels a little awkward. It’s not just two people eating. At least, not to her. In the evening, the man sees his hostess shoveling sand outside. He thinks it odd, but ignores it and calls it a night. The next morning he wakes up and sees her asleep, fully naked, on her mat. The sand in the hut and on her body is glistening by the sunlight shining in. He also finds himself covered in a thin layer of sand, so after he cleans himself with what little water there seems to be, he is ready to leave. However, outside he finds that the rope ladder he used to climb down is no longer there!

The man’s core beliefs are tested in the following period of time, as are the viewer’s. We’re basically looking at some weird form of kidnapping. There appears no way to escape, and in order to prevent the sand from killing you and to get rations one must spend hour upon hour shoveling sand in small buckets. Such a trivial, meaningless and menial task. How could anyone deal with a situation such as this? Continue to resist and fight against something you know you can’t fight forever? You need the rations to fight, and to get the rations you must stop fighting. Acceptance then, come to terms with it? But if you do, what kind of life do you really have?

The slow but steady pace of Woman in the Dunes forces its viewers to look deep down into themselves. We are said to be able to endure much more than we think we can. When put in a certain situation, we can adapt to it and make the best out of it. But we can also fight it, try to force it to change. When trapped in a dune for the purpose of moving sand every day, how would you cope? How long would you believe ‘they’ are looking for you? Weeks, months, longer? And what would you do in the meanwhile? Keep on fighting things you know you cannot change, or accept mental defeat and do what you’re told?

The story gets you right from the start an the two-and-a-half hours will be over before you know it. It’s difficult to believe that a film about two people in a sand pit could be this good, but Teshigahara pulls it off with Woman in the Dunes. At times the lack of sound, music and spoken word is giving an itching feeling. Much like the little grains of sand that constantly pour down every hole and every crack. With the exception of one piece of drumbeat music, it is mostly creepy sounds playing all throughout the film.

Now I’m not one to write about films I did not like, but in this case I couldn’t point out a single flaw even if I wanted to. The music – or perhaps sound effects is a better term – is very creepy and provides a slight horrorish vibe, much like the one found in Onibaba, coincidentally from the same year. There is little dialog, and we don’t even learn of the man’s name until the very end. It doesn’t matter, I think the director is trying to say, who he is. It could be anyone. It could be you or me. And it probably is.